The Coppola name comes with significant weight. Nicholas Cage removed it to differentiate from his uncle; Jason Schwartzmann flies under the radar within Wes Anderson pictures. Factor in the male-dominated film industry, and there must have been an enormous amount of pressure on Sofia Coppola’s shoulders preparing for her feature debut.

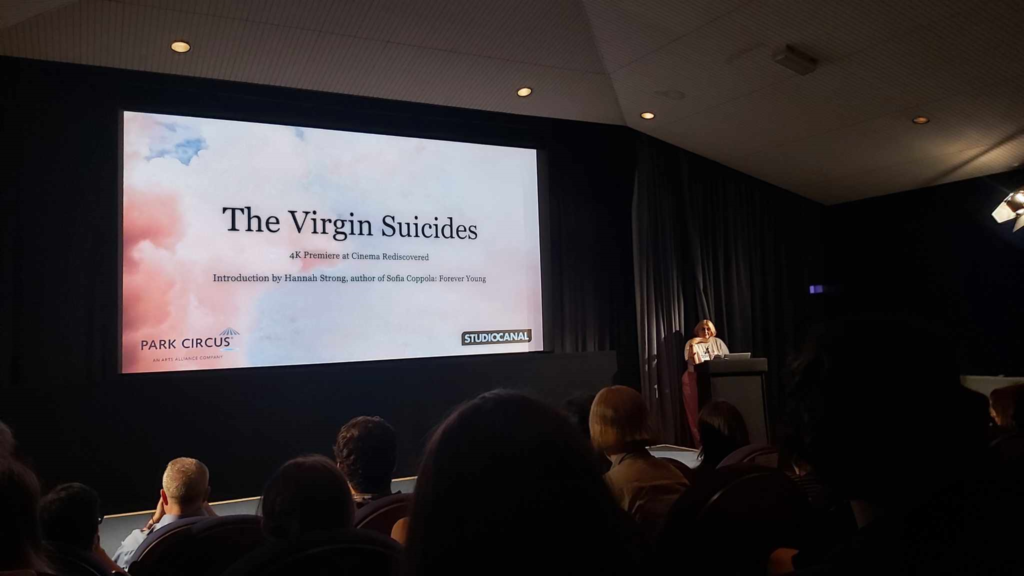

Even with filmmaking in your blood, it doesn’t make the process much easier. Prior to Cinema Rediscovered’s opening screening, Hannah Strong (author of Sofia Coppola: Forever Young and Little White Lies editor) contextualised how The Virgin Suicides was put together. Sofia’s acting performances had been critically panned and it wasn’t until reading Jeffrey Eugenides’ 1993 novel that she saw a path into directing.

Ignoring the advice of her father, Sofia wrote a screenplay before securing the rights, eventually swaying Chris Hanley into producing her script. Long shooting days were documented by her mother Eleanor Coppola, similar to Apocalypse Now with Hearts of Darkness but on a much smaller scale. A six million dollar budget would not go as far as it did for The Godfather, despite also coming with nepotism caveats. Therefore, the pitfalls present for any first-timer would also coincide with the finished product being compared to Francis Coppolas’ work.

“The result was a dreamy, devastating coming-of-age film” – Hannah Strong’s programme notes

Yet, as I watched the camera glide through Detroit suburbia, with Air’s Playground Love played on repeat in the background, it’s clear that Sofia took these challenges in her stride. Already, the visual aesthetics appear unlike most other directors I’ve seen. Seasoned cinematographer Edward Lachman’s use of travelling shots combined with nostalgic-bathed colour palettes produce an idyllic sunshine setting. Mix in old family photo slideshows, edited alongside frolicking fantasies in grassy hills, and everything feels like a dream.

With dreams, however, comes nightmares. You don’t have a title like The Virgin Suicides and expect a carefree story. The film focuses on the five Lisbon sisters (ranging in age from thirteen to seventeen), told through the lens of infatuated neighbourhood boys. After the youngest Cecilia dies by suicide, the grief-stricken household become more isolated, leading to further voyeuristic obsession surrounding these mysterious teenagers.

Such drastic tonal shifts mirror the adolescent experience. Controlled parties trying to placate their social needs are filled with humorously awkward flirting before a tragedy occurs upstairs. Moments of joyous freedom are clamped down by their authoritarian mother and backed by their hapless father (Kathleen Turner and James Woods, both with excellent performances). This is when the nostalgic lens is dropped for a colder light, facing the harsh realities of caring but oppressive parents.

Kirsten Dunst’s fourteen-year-old Lux is where the story centres around most. Her rebellious and outgoing nature catches the eye of everyone at Grosse Pointe high school, but especially Josh Hartnett’s Trip Fontaine. Driven after her initial rejection, there’s question to whether this is true love or if Lux is another prize for the football player to try and win. I found their relationship dominates a large portion of runtime, leaving the other sisters without discernible identities and the neighbourhood boys in the wings.

However, I also believe this is part of the writer’s intention. Whilst Giovanni Ribisi’s narration covers each of the Lisbon girls, the hyperfixation on Lux blankets out Mary, Therese and Bonnie, as well as the memory of Cecilia. No longer are they individuals but one object, interchangeable as they switch dates in the prom scene. Linking back to the Coppola surname, I can piece together how this would relate to Sofia wanting to break away from the preconceived expectations her family heritage presents.

Of course, this is one of many interpretations The Virgin Suicides conveys. In one sense, I’m merely projecting much like the boys in the film, so pick up Hannah’s book for more in-depth analysis. What is clear though is that the film succeeds in positing Sofia Coppola as her own director. Combine the aforementioned visuals with a 70s rock soundtrack I adore, plus intense relatable teenage themes, and you get a unique style compelled by a distinctive voice.

This would be continued in her 2003 feature Lost in Translation, resulting in wide critical acclaim and several Academy Award nominations. Whilst parallels to Francis have likely calmed down, her next feature Priscilla coming out in September will certainly face comparison to Baz Luhrmann’s Elvis released last year. Based on The Virgin Suicides, I’m sure she will stand out from the crowd again.

Watch the 4K restoration of The Virgin Suicides at Watershed or select cinemas near you this August. Thanks to Park Circus for providing the film stills. Follow the rest of my Cinema Rediscovered coverage here.